Valuing CRE - WACO

The most straightforward way to evaluate deals

In the world of CRE valuations, many investors get hung up on cap rates - a seemingly mystic, ambiguous tool - when used inappropriately. In reality, cap rates are a highly useful temperature gauge to weigh in on the market's sentiment for an asset class. In lieu of other CRE investment opportunities to compare cap rates against, they mean nothing. Also, in lieu of other investment opportunities like equities, annuities, and fixed income products, cap rates again, mean nothing.

Investing in general is only relevant from a relative value perspective. Investors are aiming to achieve a return that is warranted given their perception of the risk in light of an analysis of objective historical data, and future assumptions as to how the deal will operate.

Cap rates are one useful tool used to value CRE, but they are not perfect (nothing is). I wrote in a previous article how cap rates are derived from subtracting an annual growth rate assumption from a computed discount rate. While that is good and all, it doesn't capture the full picture.

Weighted average cashflow obligations can help fill the void the cap rates leave us... mainly because they are detached from future assumptions. They focus on the math today, and the achievable return on equity through cashflow. Cashflow matters more than anything because ultimately, without growth, that is all that is left in your return. Growth certainly doesn't always occur... cue the last few years.

So, what is the buzz about WACO?

Weighted average cashflow obligations (WACO) are the most cut-throat way to value stabilized real estate deals AND green light exit assumptions by computing your prospective buyer's math.

WACO calculates the yield (NOI) required to meet financing obligations to various equity and debt providers.

First questions to ask: how much debt does this property support?

Secondly, does the asset generate enough cashflow to cover debt service and hit my minimum equity cashflow hurdle?

Investors are all paying for cashflow streams, chasing after mis-priced streams to generate outsized returns.

After quickly sizing for an asset's permanent debt capacity based on trailing financials, you simply determine what your stabilized CF requirement is on your equity based on your risk tolerance. Then you blend the two together to determine the price a property's NOI can truly support.

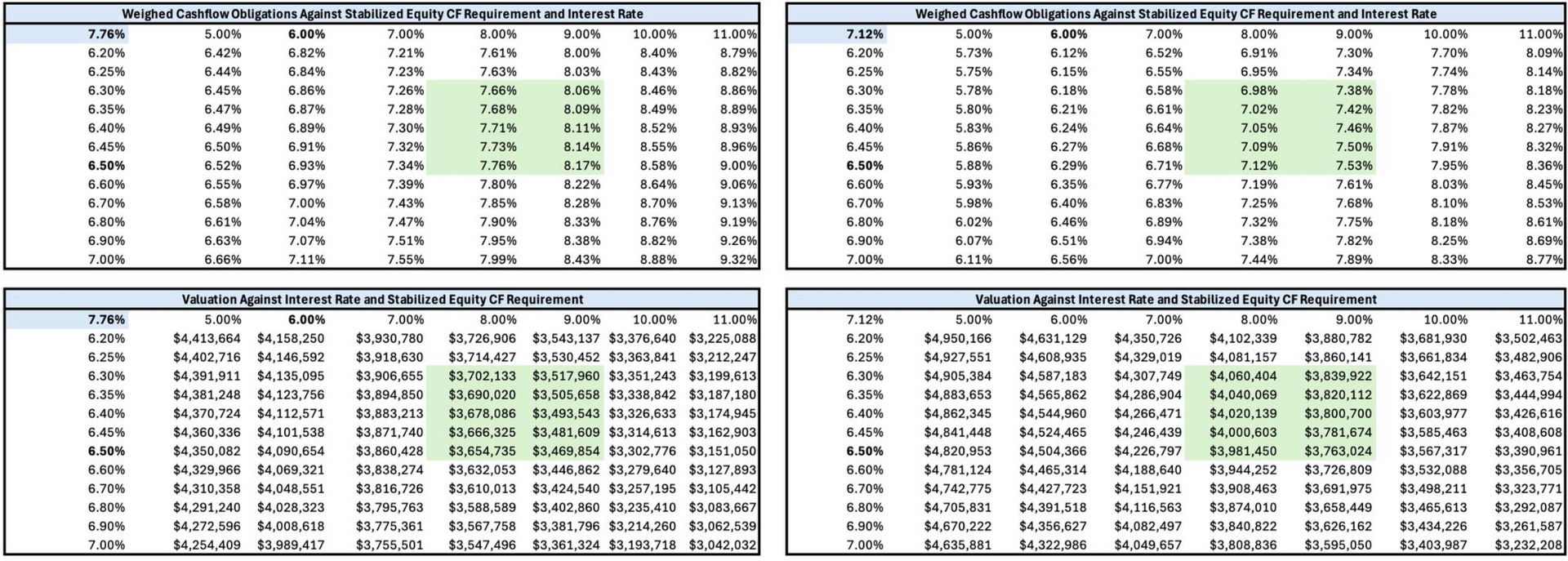

In the example illustrations below, you can see a sample class C multifamily asset. On the left hand side, you will see WACOs based on amortizing debt. Column is your interest rate, and row is your equity CF hurdle. On the right hand side, you will see WACOs based on interest only debt. In multifamily and especially institutional multifamily assets, you can get programmatic interest only, and in some cases, full term IO. Therefore, it isn't quite accurate to value the property based on its amortizing debt obligations. Bidders with longer debt terms will likely get more IO quoted, so they will be able to solve for a higher price since they need less NOI to cover annual obligations on each dollar.

Each dollar of a project's total cost will have an obligation tied to it. NOI will be allocated towards paying debt service or paying equity partners.

In this case, at a hypothetical 6.5% rate, and an 8% stabilized equity CF yield requirement, a buyer with interest only debt is able to pay 8% more than a buyer levering up with no interest only, all other things equal. Yes, this is overly simplified, but it also makes a lot of sense.

I am leaving out growth assumptions, of course, which can't be understated. Properties end up trading for more in sellers' markets because bidders will stomach underwriting higher growth through the hold period to meet their returns. For example, they may price the deal by solving for an 8% equity CF hurdle, but they may accept 4-5% day 1 if they buy into the assumption of rental growth. As we have seen these past few years, you certainly cannot always do that.