Blog: Don’t Forget About Supply

With national multifamily deliveries hitting 50 year highs, many operators and developers are questioning whether or not current and future values are defensible due to operational and capital market headwinds in the current environment. Rising supply and demand imbalances pose a a threat to revenues, collections, and occupancy levels. Many growth markets are experiencing 20-year high supply deliveries which will temporarily soften tenant absorption and therefore revenue + property values. High supply and a weaker consumer will drive lower occupancy, rents, and higher concessions until the new supply is absorbed. Once it is, we should be trending back to a normalized annual rent growth environment on average, in positive net migration markets.

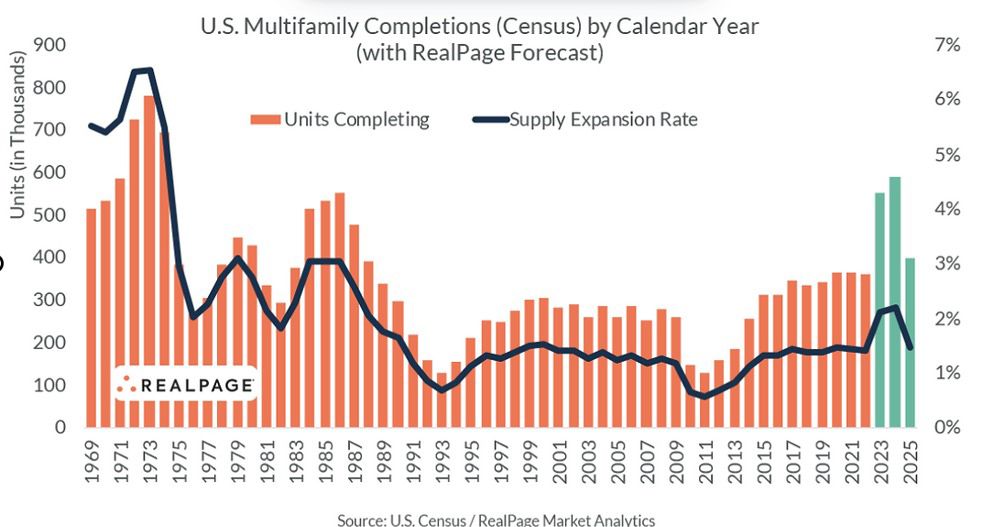

U.S. Census/RealPage Market Analytics

Although on an absolute basis, deliveries are hitting 50-year highs, it is more important to consider the relative supply expansion rate. Our country is still short on rental units, and the recent exorbitant spike in debt financing will likely weigh on new deliveries from 2025 and onward. Taking the news headlines at face value could lead to missing out on a functionally advantaged time to develop. Demographically, our country looks a lot different than it did in the 70s and 80s. Today's developers are delivering units to a much larger pool of renters. As a result, lease up distress will hit markets much more selectively, depending on the relative expansive rates and employment strength in each market.

How do developers know when to stop developing? Developers are usually solving for a 30%+ gross margin on new projects. Typically developers will overdevelop a submarket/market due to the lag between pre-development/entitlements and lease ups. As everyone wants to participate in an area's rapid growth, developers all race to bring units online at the same time, usually resulting in a cascade of oversupply, triggering a local market down cycle once absorption (growth) taps out. More supply will force competitors to lower rents, leading to falling revenue, decreased NOI, and lower property values. Once the math breaks and projected profit becomes too thin - developers will halt new projects. So what's in the 30% margin? To calculate that margin or profit, developers need to quantify their all in costs and their end value.

Construction pricing is the largest input in determining replacement costs for real assets. Replacement cost analysis is an important fundamental to understand as it generally sets the value for new core assets, thereby affecting asset values down the property grade chain. From 2018 and onward, apartment pricing for older assets began to skyrocket, climbing above replacement cost for buildings built between 2000 and 2020, by as much as 20-30% in some cases. The market was over-valuing these assets. It doesn't make sense to pay a higher price for an older asset if you can build it for cheaper.

Generally, investors require a discount to replacement cost for existing assets that is commensurate with the added risk and capital outlay these older buildings require to service, maintain, and keep full. This inflated pricing dislocation was a reflection of hot demand and rental growth, lots of capital, and cheap debt, compressing cap rates and pushing values to record-breaking highs.

Another forward looking indicator for over-valuations is the cap rate spread across same property type asset grades. Typically, apartments trade at a 200-400 basis point spread from A-D asset classes, with nicer assets located in the best areas commanding the lowest cap rates and vice versa. Over the past couple of years, however, that spread narrowed to near 0 in the hottest markets in the country, an indication of broken fundamentals and overly-eager underwriting expectations. These lower quality assets are likely to see a harder hit to their valuations than their counterparts until they revert to their mean values.

Because existing assets were overpriced and buyers were willing to pay up to 30% over replacement cost, the ball has been in the developers court these past few years. Developers could command anywhere from 30-50%+ gross margins on projects, fueled by an expansive, low rate debt environment allowing these buyers to solve for an abnormally low WACC and resulting high price. Gone are the days of 5,000 year interest rate lows.

Let's take a look at some of the leading indicators driving the cost for new construction to better understand what drives pricing.

1) Energy

Petroleum is the most important input cost for all of our finished goods since these goods require energy to transport and build them. Construction is no different. Hydro carbons/oil have dominated the world energy game fueling growth and productivity over the last couple hundred years. As global energy trade and production shifts significantly, we are likely to see more volatility and higher costs. Higher energy costs means higher pricing for goods and services as these costs are passed down to the consumer.

2) AIA/Deltek Architecture Billings Index (ABI)

This index tracks the demand for architectural services, a leading indicator for construction projects. A score below 50 translates to less demand than the prior period, and a score higher than 50 translates to more demand than the prior period.

3) Steel, Lumber, Concrete, Copper

These are the most common raw commodity inputs for construction projects forming the structure and electrical components of buildings.

4) Associated Builders And Contractors Indexes (ABC)

ABC is a national construction trade association and tracks construction sentiment through indexes and reports such as the construction backlog indicator.

5) US Census Bureau Construction Spending Data

This data breaks down national construction activity by product and industry type. Although it is lagging, it is reliable reflection of trends and future sentiment for the industry.

6) Producer Price Index (PPI)

A bundle of indexes that measures price movement from the seller's perspective. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics has a specialized graph that tracks construction specific data. See chart below.