Blog: A Strong Case for Private Credit

In the latter half of 2022 and into 2023, capital flew in droves to money markets and short term treasuries as higher than expected inflation forced the Fed to invert the yield curve with a round of historically sharp interest rate hikes, pushing the short rate (SOFR) to 22 year highs.

Although inflation was largely an issue of constrained supply with lingering COVID-19 supply chain issues, the Fed needed to act in response to pressure so they could satisfy expectations. This move effectively bankrupted the banking system because prior to covid, the FEDs sentiment and telepathy was low sustainable 2% inflation and low rates to stay along with it. In response, banks and various companies in the business of producing safe returns to meet financial obligations were encouraged to invest/lend long in search of bonuses and yield spread. Unfortunately, not many of them hedged their interest rate risk.

The sudden increase in risk-free rates of return are throwing equity markets for a spin, sucking liquidity out of the banking system, and threatening risk asset values as well as fixed income alike.

Increasing risk-free yields are putting upward pressure on existing variable loan servicing costs through higher annual debt servicing, stressing real estate free cashflow, (variable loans are priced at a spread over the SOFR index), and they are also forcing investors to scrutinize their yield & growth expectations. Ultimately, cap rates are expected to expand to meet the risk-reward expectations in the market. How much they will expand, if any, is a function of capital flows and future growth expectations. This comes at a time when inflation is putting upward pressure on operational expenses such as taxes, insurance, energy, utilities, precious metals, and labor.

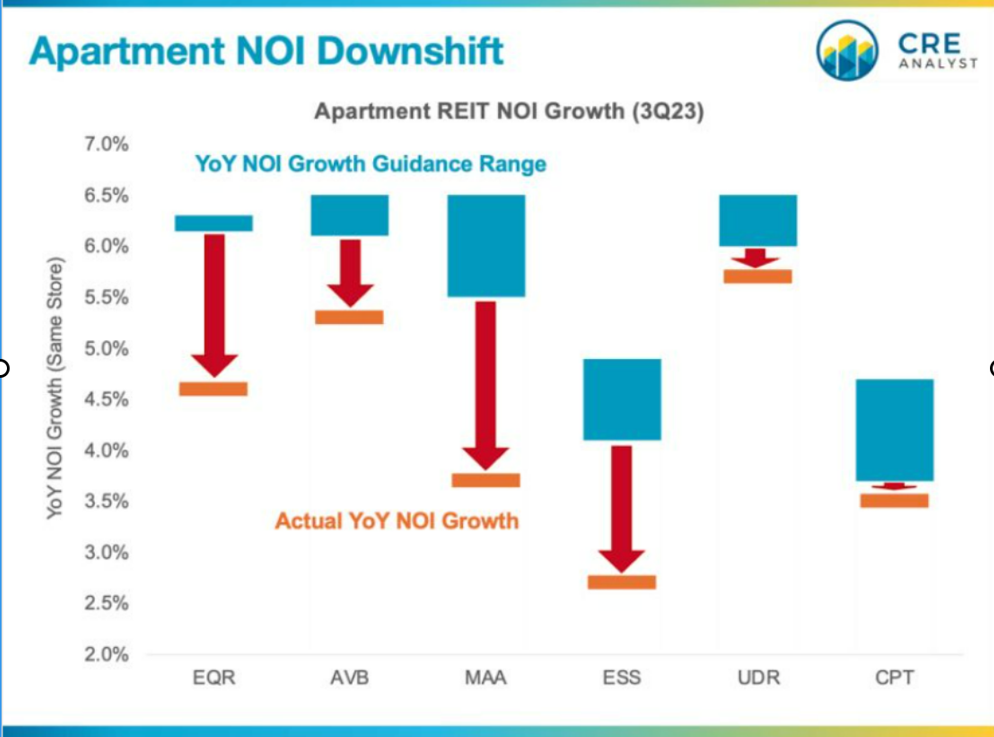

The resulting effect? Decreased NOI, lower property values, and a large disconnect between buyers and sellers. In many primary, secondary, and tertiary growth markets, expense growth has outpaced revenue growth year over year and threatens to do so through 2025 based on forecasted growth outlooks in select markets. Several Apartment REITS have reported lower than expected Q3 earnings due to revenue and expense pressures suppressing net income growth. On average, NOI across $100B of major apartment REIT values has missed projections by 28%.

The body content of your post goes here. To edit this text, click on it and delete this default text and start typing your own or paste your own from a different source.

Source: CRE Analyst

Investors who put bridge debt on assets in 2021 are under immense pressure to takeout their loans that are coming due this year and next. Given that NOI is down and cap rates are up, it is becoming increasingly hard to refinance these loans without the borrowers infusing cash into deals. Over the last decade, investors became accustomed to cash-out refinances, in which new loan proceeds exceeded that of the old loan amount, creating equity and value for partners. With interest rates climbing and threatening to remain elevated, we may see a wave of deals whose NOI are not high enough to support leverage that exceeds principal loan balances.

Multifamily values have come down from their peak, anywhere from 15-25%, depending on the market, asset class, and property level grade + characteristics. But since the private market and real estate in general is relatively illiquid, sellers can hold to prevent portfolio mark-downs and losses, just as long as they have good debt. The public REI market trades based on expectations and given its liquid nature, it tends to be a forward looking indicator for the private real estate markets.

In almost all of 2021, SOFR remained at 0% and the 10 year hovered under 1.5% for the majority of the year. Core, new multifamily assets in growth primaries traded as low at 3.25-3.5% cap rates.

Fast forward to 2023, and SOFR stands tall at 5.3% while the 10 year stands at 4.63%, an exorbitant increase, the sharpest rise in multiple decades. This increase in debt capital helps explain why sellers are not meeting the value expectations of current buyers in the marketplace. Buyers are underwriting to a much higher weighted average cost of capital, and sellers are in denial when you tell pricing is down 15% + from their expectations just months ago.

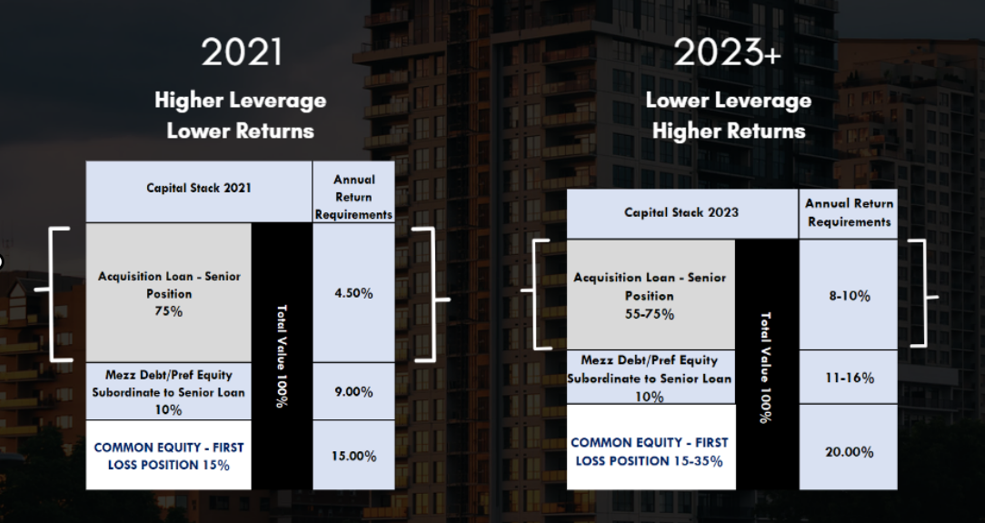

In time of value uncertainty, it pays to move down in the capital stack. Defensive positioning can help insure capital remains hedged from material swings in value, holding its value until the market heads back up. The chart below illustrates the changes in capital financing and return requirements, as well as leverage demands.

In the chart above, you can assume that the first position loan is a bridge loan. Once the Fed raised the short-term interest rate in one of the fast rate hiking accelerations in history, values began to wither, leverage receded, and equity became more hawkish. Weighted average costs of capital increased, putting pressure on free cashflow, valuations, and newly sized loan proceeds.

2021 rewarded investors for taking on more risk, sitting in a common equity position. It was common to see 15-20%+ annualized returns for vintage multifamily deals bought at reasonable prices and resold or flipped 2-3 years later. Many of these properties produced even higher equity returns, producing MOICs of 2-4x in less than 3 years. A combination of compressed cap rates and historically high rent growth produced these returns.

In 2023, case dependent, investors can command equity-like returns for debt-like risk, sitting in a preferred equity position in the stack. Similarly, senior first position lenders can command equity like yield while receiving a higher margin of safety on their leverage position. This capital stack dislocation became larger as debt-capital from banks dried up, and its expected to get even worse, leaving a gap and opportunity for those that are able to see it. Equity has to offset the decrease in leverage, hurting projected returns on much larger tranches of equity, driving yield expectations up even higher and pressuring values.

The risk-reward ratio largely favors credit or preferred equity in this environment because investors can earn a higher return for much less risk. We call this asymmetric, meaning, your potential for upside is higher than your risk of downside.

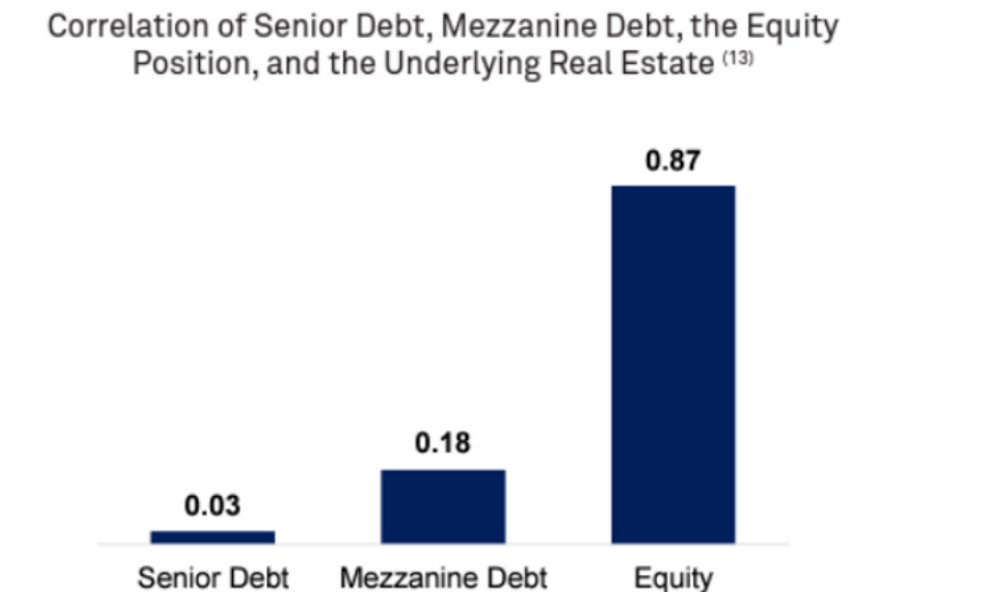

Historically, debt is uncorrelated to the value of the underlying real estate itself, as shown in the image below. AEG believes that debt and preferred equity is the most attractive vehicle at this point in the market cycle; although, equity opportunities are just starting to be compelling.

Once the market has confidence in future inflation, then it can rely on a terminal rate in order to confidently move forward with trades. Real estate transactions rely on an efficient and liquid banking system to function - & when debt dries up, appraisers and buyers alike cannot rely on prior trades to establish values... and lenders are not issuing any favorable term sheets either with deteriorating property and capital market level fundamentals. The result is a chain-effect of pressure build up.

Since bank debt issuance is a function of healthy collateral and reliable markets, we are likely to continue to see turbulence until something breaks or the Fed lowers rates. Until/if then, it will pay off to be lower in the capital stack as investors look for alternative debt solutions to fill the gap left by traditional lenders.