2025: The Wild West

Where Have We Been, And Where Are We Going?

2025 Macro Predictions

1) High investment volatility in the backdrop of converging geopolitical and economic forces, making it difficult to forecast real growth and price risk across all investments.

2) Sustained higher interest rate environment amidst sticky inflation. Rates are unlikely to drop back to pre-pandemic levels. Investors demand higher compensation in exchange for taking fixed income risk during times of instability. Inflation may not ‘stabilize’ to a mean like it has historically but if it does, it should be higher than the 2% historical average.

3) Government spending and fiscal deficits will increase which will impact the supply and demand of treasury bonds, a baseline index that materially impacts the price of commercial real estate. Heightened global unrest and political / social instability will increase pressure to invest in national security. Public and private investment into the low carbon transition, AI boom, energy infrastructure, healthcare sector, & food sector will all increase significantly.

4) Private credit will continue to dominate CRE lending market share as banks work through their balance sheet issues. Banks will not be a large player in our space again until office price discovery is fully realized.

5) Elevated wage growth, fueled by more restrictive immigration policies to come, will aid residential and commercial real estate net operating income growth in the wake of our aging working population.

6) More sensitive equity capital across the stock market and alternative investments such as real estate. This will lead to price volatility and shaky sentiment following big market/geopolitical events.

7) Higher interest rates will restrict new supply, making it difficult for developers to meet the demand of renters and buyers of housing in high growth markets. Home prices and multifamily values will rise in desirable areas. This will make the Feds job of controlling inflation even more challenging, since > 30% of the CPI is derived from housing.

8) More liquidity, more transaction volume, higher nominal asset valuations. Currency will chase alternative assets with a more fixed supply, such as real estate. Some CRE asset classes will produce real returns. Others will be slower to recover from earlier highs but may still track 1:1 with the expansion of the money supply (inflation).

9) Greater institutional investment into land development, data science centers, affordable housing, and untraditional CRE assets. Greater experimentation, access, and adoption into tokenized real estate investments.

10) The rise in treasury rates will be somewhat offset by reduced credit spreads (higher credit competition) and higher growth expectations from investors. Reduced correlation between interest rates and cap rates is likely. Anticipated historically low spread between 10-year treasury and cap rates for multifamily.

Let's remind ourselves of where we have been and where we might be going...

Over the last five years, the CRE industry has witnessed unprecedented developments. In 2020, the Fed made borrowing almost free to curb a severe market disruption and record-high unemployment (14.7%) caused by the pandemic and global supply chain related issues. However, beginning in March of 2022, the Fed completely reversed its stance by raising interest rates 11 times to combat inflation—an inflation they significantly contributed to through various money printing and liquidity measures. To make matters worse, in the summer of 2021, the Fed misled the market by labeling inflation as transitory, assuring that rates would stay low and encouraging investment at those lower levels. Don't you just love when the Fed tries to prevent pain in the market? Every time they try to prevent a market crash, they end up hurting the free market much worse in the long run, and we all get to pay for it. Yippee. We are all waiting for the day austerity gets to play its course, but the political threat of an economic deleveraging will keep the Feds foot on the money printing pedal for as long as humanly possible, so we think.

As a general reminder, Fed likes to issue debt below the growth rate of our economy so they can pay the debt back with cheaper dollars later. But the merry-go-round of “fake growth” always comes to an end, historically. And central governments such as ours are up against pacifying the public so they can remain in office, satisfying their public mandates of maintaining low employment / price stability, and fueling their selfish desires for power, greed, and wealth. Without real economic growth though, it is all a house of cards, and the fall is a matter of “when” not “if”.

Okay. So what happened to real estate, and where are we now?

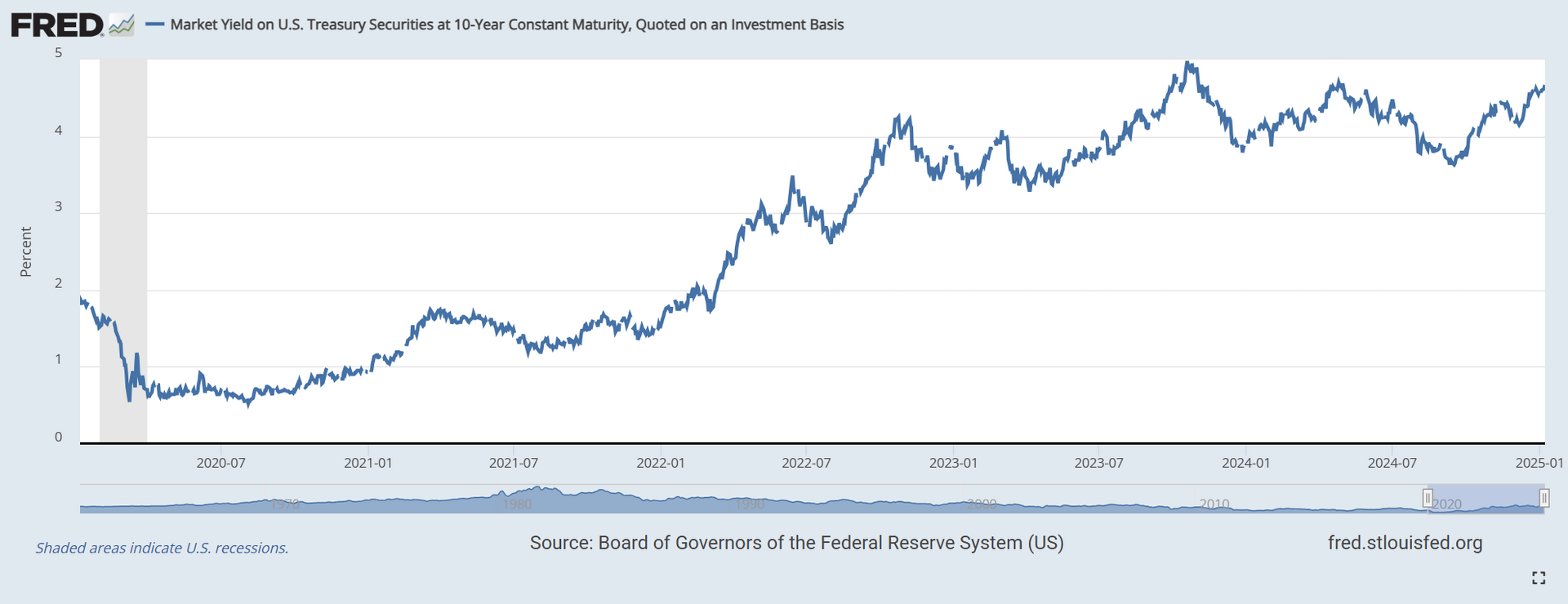

Investors loaded up on this cheap debt. Banks loaded up on cheap bonds. Institutions issued cheap debt and then sold that debt to other private and public entities. The entire market fell to recency bias, believing in the Feds messaging that rates and inflation would remain somewhat low. 60% of the total US dollar supply was created since the pandemic, and this printed debt chased assets and products, inflating them on paper at unhealthy levels. The only problem? People were not working or being productive to service this debt. Instead, millions of Americans received printed helicopter money. Some saved it, others spent it. Cheap debt allowed real estate investors to solve for higher prices, and we saw astronomical asset peaks, well above the cost to replace these assets brand new. A red flag of overvaluation. Without real growth in net operating income, the nominal price growth was unsustainable. Suddenly in Q3/Q4 of 2021, inflation was not transitory, but the Fed was playing with fire and opted to wait too long to raise interest rates to curb demand. From March of 2022 to July of 2023, the overnight borrowing rate increased from 0% to 5.5%, marking the largest rate hike acceleration in recent history. This is the rate at which banks can borrow from the Fed. At the same time, the 10 year treasury went from 1.7% to nearly 4%. See the chart pictured at the end of the article.

And the result? Broken mechanics across the entire investment industry since market participants are reliant on debt to fund their business capitalizations. The worst bond selloff since 1787. Bond investors wiped out, major pricing resets, and substantial 'implied' equity losses. But, lenders and investors alike believed in a light at the end of a super short tunnel, so they kicked the can down the road as most people would. Instead of foreclosing on borrowers and writing off bad loans, they played the extend and pretend game waiting for the Fed to lower rates and fix the mechanics to bail them out of their hole. Well, the Fed didn't follow through with the rate cut bail-out in the way we all expected. Instead, they reached out their hand just to let go and push us deeper into the hole.

These massive rate hikes caused tectonic shifts in risk and reward expectations in the capital markets, largely stalling investment activity in 2023 and 2024, and that brings us to where we are today… much lower rate cuts than expected due to stickier inflation. The Fed began lowering the Fed Funds rate in September of 2024, and they have made a total of 1% in rate cuts. More importantly, though, is how fast future expectations for inflation changed in just months. The Feds went from baking in a 3%-3.5% landing zone range for Fed funds in 2025 to 3.75%-4%. Investor expectation followed suit. If you go back and look at the SOFR Forward Curve in July of 2021, the market's projection of short-term rates (closely linked to Fed Funds) were just around 1% through 2027. Fast forward to the end of last month, and projections are now hovering around 4% through 2027, a massive swing in sentiment around inflation expectations. It is no surprise that this caused major dislocation in the marketplace.

As a result of the short-term volatility and structural forces at play disrupting the business cycle that we all thought we were subject to, investors have shown heightened sensitivity to long-term assets such as longer dated treasury bonds. Risk becomes harder to price when inflation eases but growth persists. There were and still are several variables at play each interacting with one another. Traditional 60/40 stock and bond portfolio allocations, like the ones we are all used to hearing about from investment advisors, are unlikely to meet the needs and goals of investors going forward.

We are entering into an era of systemic and structural shifts as central governments look to position themselves for security, growth, and value creation in the wake of heightened volatility.

It is safe to expect a rather wide range of potential growth and investment outcomes in 2025 and beyond. Our thesis has pushed us to be proactive in our approach to altering our investment strategy, prompting us to shift more heavily towards land development as well as more secure investment positions like direct lending.

We expect higher transaction activity, greater liquidity, elevated interest rates, and fragmented cap rate spreads across the commercial real estate investment market in 2025 as investors place their risk-adjusted bets.